1942 Trainwreck

Southwestern Limited Trainwreck of 1942

Ashmore, Illinois

Note: this is a collection of excerpts from the Accident Investigation Report, rearranged for brevity and logical order. The blue text is not verbatim excerpt from the report, but instead this author’s own words, based on terminology research and understanding of the incident. For a more detailed account of the accident including technical descriptions of the malfunctions and human errors leading up to the accident, please refer to the complete report available at the bottom of this page.

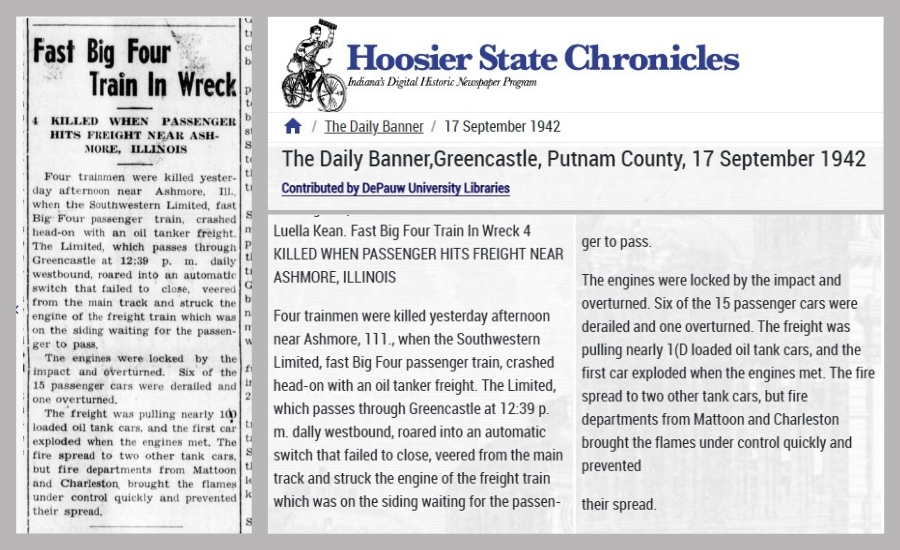

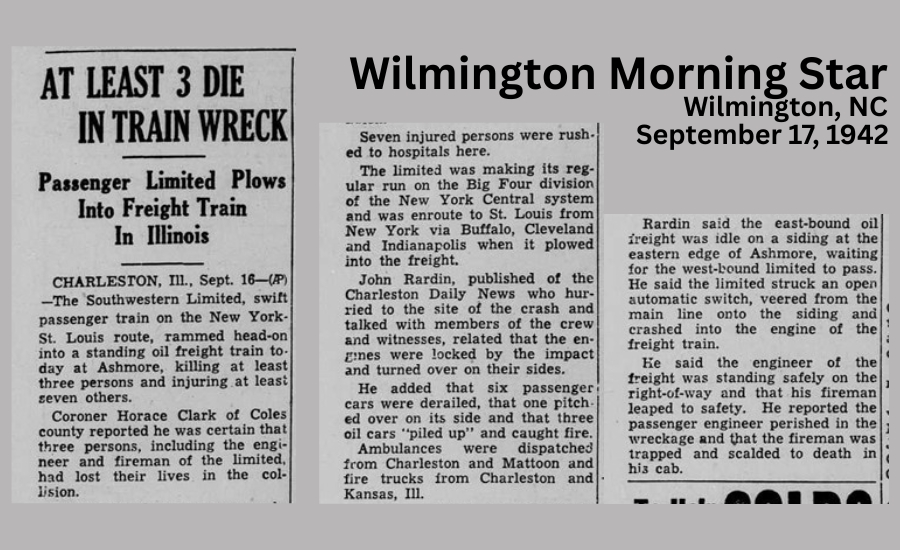

On September 16, 1942, there was a head-end collision between a freight train and a passenger train on the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis Railway at Ashmore, Ill., which resulted in the death of 1 express messenger, and 2 train-service employees, as well as the injury of 14 passengers, 2 railway-mail clerks, and 4 dining-car employees.

Third 80, an east-bound second-class freight train, consisted of engine 2142 followed by the tender car, 49 loaded cars, and a caboose. This train entered the eastward siding at Ashmore at 2:29 p.m., and stopped with the front end of the engine 436 feet west of the east siding-switch. About 45 minutes later the engine was struck by No. 11.

No. 11, a west-bound first-class passenger train, consisted of (in this order) engine 5384 followed by the tender car, 1 mail car, 1 express car, 1 passenger-baggage car, 3 coaches, 6 Pullman sleeping cars, and 1 dining car (15 cars total).

Description of the Railway at the Ashmore Station

The main line of the railway is a single-track line passes through Mattoon, Charleston, Ashmore, Kansas, and Indianapolis, among others. During the 30-day period leading up to the accident, the average traffic at Ashmore was 45.76 trains per day.

At the Ashmore Station, there is a 2nd track that is connected to the main line and runs parallel to it on the north side of the main line, called the “eastward siding.” This is where trains can pull off to the side, so to speak, so that another train can pass through on the main line.

Where the siding track meets the main line, there is a section of track that moves, called a “switch.” The position of this switch determines whether trains physically stay on the main line or are diverted to the siding track.

Looking east from the Ashmore Station, the East Siding-Switch was 4,832 feet (0.92 miles) from the station. There was also a West Siding-Switch to the west of the station as well as dual Crossover switches right at the station, but in this narrative they are irrelevant.

As a train approached the station from either direction, it passed two light signals. In a time before cell phones or ham radios, the colors of the lights communicated to the train engineer about how to approach the station and whether to stop on the siding track. The switch and the signals were controlled by the “operator” from inside the station using 10 levers. While the operator stayed in the station, the lights were serviced by the “signal maintainer.”

A west-bound train, approaching Ashmore from the Kansas, would first pass the “Approach Signal” (aka “Approach Signal 1061”), which was 9,244 feet (1.75 miles) before the East Siding-Switch. Approach Signal 1061 gave the engineer one of four commands:

- “Proceed,”

- “Approach” meaning “Proceed approaching next signal at medium speed,”

- “Proceed preparing to stop at next signal,” or

- “Stop, then proceed at restricted speed.”

As the train would continue towards the station, it would then pass the “Home Signal” (aka “Home Signal 1071”), which was just 60 feet before the East Siding-Switch. Home Signal 1071 gave the engineer one of five commands:

- “Proceed,”

- “Approach” meaning “Proceed approaching next signal at medium speed,”

- “Proceed preparing to stop at next signal,”

- “Proceed at restricted speed,” or

- “Stop.”

Leading Up to the Accident

No. 11 [passenger train] departed from Indianapolis at 1:10 p.m., 1 hour 8 minutes late, then passed Kansas at 3:10 p.m., 1 hour 19 minutes late. During that time, about 1:35 p.m. it was found a failure had occurred, causing the indicating lamp to be lighted continuously. The operator on duty informed the signal maintainer of this condition, and he immediately started to look for the cause. At 2:37 p.m., the maintainer and his helper went to the depot and were engaged in checking the circuits for about 10 minutes.

A new operator came on duty at 3 p.m. Moments later, the maintainer and his helper returned to the east siding-switch and conducted tests to ascertain the cause, but the fresh operator was not aware of what the maintainer was testing. About 3:07 p.m., the maintainer instructed his helper to call the operator at Ashmore by telephone and to tell him to move the lever 1 to center position and then to move it to normal-indicating position. The front brakeman of Third 80 [freight train], who was near the relay housing, heard the maintainer tell his helper this; however, the helper, who had had but little experience and did not fully understand signal terminology, said he instructed the operator to place lever 1 “in neutral position.” The operator was not certain what was meant by neutral position, but after some delay he placed the lever in center position. [He did not, then, place the lever in normal-indicating position after, which is what the signal maintainer was expecting to be done.]

When No. 11 [passenger train] was approaching Ashmore, the signal maintainer was distracted making a study of the circuit plans. The front brakeman of Third 80 reminded the maintainer that the switch was lined for the siding. The maintainer continued his work on the plans and relays for a time, and then instructed his helper to line the switch manually for main-track movement. The helper endeavored to throw the switch but could not move the selector lever. The maintainer went to his assistance, but neither the maintainer nor his helper was able to line the switch for the main track.

Meanwhile, No. 11 passed approach signal 1061 at a speed of 59 miles per hour. No surviving member of the crew of No. 11 observed what indications were displayed by signals 1061 or 1071. However, the investigation disclosed that this train received a “Proceed” indication at Approach Signal 1061. The speed-recorder tape indicated that 8,127 feet (1.54 miles) later, No. 11 had increased speed to 67 miles per hour.

[By this point, someone had noticed that No. 11 was fast approaching down the track.]

The front brakeman of Third 80 and the maintainer then started eastward to flag No. 11; however, because of the speed of the approaching train, the flag protection was not provided at a distance sufficient for No. 11 to stop fast enough.

The speed-recorder tape indicated that a heavy application of the brakes became effective at a point about 1,057 feet east of home signal 1071, and the speed was reduced from 67 to 55 miles per hour in a distance of 1, 533 feet.

Description of the Accident

The weather was clear at 3:15 p.m., when No. 11 (moving 55 miles per hour) struck Third 80 (sitting still) head-on.

Engine 2142, of Third 80, was driven backward about 100 feet by the impact. The engine and tender were overturned on their left sides, north of the siding track and parallel to it. The front end of the engine was crushed inward about 5 feet and the cab was demolished. The first three cars were derailed, the oil with which they were loaded became ignited, and they were destroyed.

On No. 11, Engine 5384 and its tender were derailed and stopped on their right sides, north of the siding track. The cab was demolished. The first car (mail) was derailed and considerably damaged, and it stopped on its right side. The second car (express) was demolished. The third through seventh cars (passenger, coaches, & 1 sleeping car) were derailed and considerably damaged. The eighth car (sleeping) was slightly damaged. [By this author’s deduction, 4 sleeping cars and the dining car remained on-track and upright.]

The train-service employees killed were the engineer and the fireman of No. 11.

Dr. Donald B. Sanford

Video footage was captured in the aftermath of the train wreck by a soldier named Dr. Donald “Don” B. Sanford, who happened to be travelling on the train. Dr. Sanford’s son, Donald P. Sanford, found the footage among his late father’s belongings and had it digitized. Mr. Sanford graciously contacted Ashmore about his findings and sent a copy of it home to Coles County.

The full footage is available on YouTube at this link: https://youtu.be/aZk_u7itRIo

The accompanying letter from Mr. Sanford states:

April 16, 2025

Dear Ashmore,

Thanks for your interest in my dad’s film.

My dad was a surgeon attached to the 52nd General Hospital. He and his unit were enroute from Syracuse, NY to Camp Livingston, LA when their train was wrecked near Ashmore on September 16, 1942.

He was an avid photographer and filmmaker. He always had his cameras handy. Fortunately, amidst what must have been a chaotic day, he remembered to shoot this footage.

The original film is 8 mm. I had it digitally scanned at the University of Wisconsin’s film preservation lab. I made the color corrections.

I hope you and your historian friends enjoy it.

Sincerely,

Donald P Sanford

Related Documents

- ICC Washington - Investigation Report of Ashmore Accident ( PDF / 838 KB )